It’s been a year of highs and lows in the games industry, much of which felt like the long tail of the Covid pandemic wagging around in unexpected ways. A lot of great games came out this year – many of which have probably benefitted from delays and changes to working arrangements during the pandemic. In spite of this we’ve also seen a huge number of layoffs and studios closures, and my single-post-it-note summary would be that the games industry went through a demand bubble during the pandemic, big investors moved to try and claim a piece of that action, and then as Covid died down the bubble burst, and suddenly a lot of big belts needed to be tightened.

As a result, it’s been a banner year for quality games and revenue has often been good, but at the same time we’ve seen an astonishing number of layoffs – somewhere in the region of 7,000, according to Polygon.

As for myself? I appear to be doing okay. I don’t like to post about work, but I made a great spreadsheet earlier this year. Following up on my new years resolution from last year, I read five books and started going swimming again. I painted a Frostgrave warband (a collection of halflings I bought from Midlam Miniatures) and upcycled some vintage Eldar models in preparation for the new edition of Warhammer 40,000. I grew some excellent chili peppers, slow-cooked a lot of curry, and put together some new raised beds to grow more strawberries and raspberries next year. I bled a radiator.

I streamed the entirety of Tears of the Kingdom on Twitch, with zero commentary – I think it was about 130 hours over a three-week period, which is a little alarming considering that I was fitting it in around a full-time job. It was the most significant effort I’ve made to stream anything, and even at the time I thought…. this must be extremely boring to watch, right? I feel like it was an interesting and worthwhile experiment at least, but my biggest takeaway was that you really need the player to be describing their thoughts and intentions sometimes. Or at least, that’s what I would want. I learned a lot of (admittedly very basic) stuff about how Twitch works from a creator’s perspective too – like how I need to reach a certain minimum cadence of streams and viewer numbers or else they’ll delete my videos after a few weeks. Still, I have a few nice clips to look back on.

But enough of that; let’s review what I’ve been playing.

Tunic

Tunic is a delightful action-RPG that tries to recreate the sense of mystery of older games like The Legend of Zelda and then transplant in some modern gameplay loops cribbed from games like Dark Souls. I didn’t finish either of those games and I didn’t finish Tunic, so maybe it worked.

I did really enjoy Tunic, particularly the way that it slowly explains how to play by way of unlocking pages from a NES-era instruction booklet. It’s reaching out to things that were part of the videogame experience back in the late 80’s, but which have been sanded off and streamlined through better technology and smoother UX design – like how it feels to play an imported game in a language you can’t read, so you have to decipher the instructions through trial and error. It’s cute, it’s mysterious, it’s got simple-but-deep-ish combat; I did really enjoy it.

This was supposed to be the paragraph where I talk about what I didn’t like about the game, but really the only reason I stopped playing was because I couldn’t beat some of the bosses (the Boss Scavenger and the Librarian, for those who care) and got tired of bouncing off them. I suppose my design analysis would be something like… the difference in difficulty from the regular enemies to the boss fights feels too large. Maybe the solution could involve having some encounters where I can get a better understanding of the upcoming bosses’ attack patterns and tactics, but in a smaller / slower / more manageable setting? There’s some amount of this tutorialising going on already, but clearly not enough for my brain.

But then, that’s just the sort of thing that Tunic is in conversation with – how standards of friction have changed in games over the last 40-odd years. Smoothing out the difficulty curve so that players don’t feel overwhelmed by a sudden spike is kind of a modern, ultra-processed fast food approach to game design… which probably leads to players feeling more competent and liking your game more, but also strips away some of the weird, sharp edges that can make a game feel distinct.

Pentiment

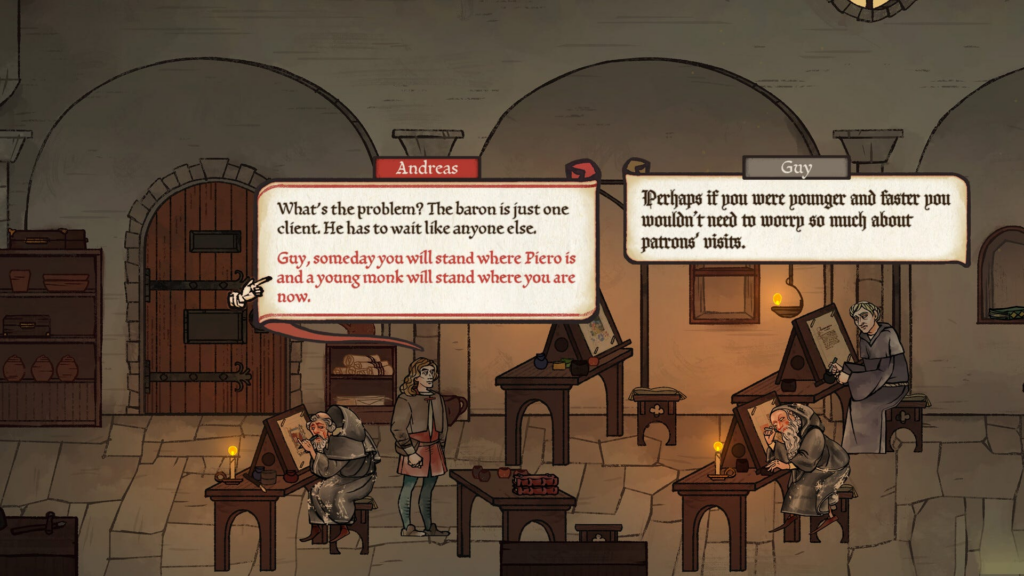

This was an interesting game! One of the standout trailers from last summer, Pentiment is a sort of old-school adventure game where you play as a wandering illustrator in 16th century Bavaria, who is hired to illuminate some manuscripts at a prestigious (but cash-strapped) monastery and ends up getting sucked into a Cadfael-esque murder mystery. As you explore the town and discuss the events with locals, you uncover lots of overlapping tensions around the political structure of the empire and the church, and the impact of new technologies (namely, the printing press) on traditional forms of labour.

It reminded me of Telltale’s games (eg. The Walking Dead) in the sense that you’re constantly being maneuvered into complicated problems with no ‘correct’ answer – if you’ve dug around and done your research, you can see that every available option will cause a problem for someone, so it’s a game about deciding where you’re willing to make the cuts. Who are you going to kick off the lifeboat? What do you suppose will happen next? It never felt particularly difficult in the videogame-y sense, but it was a complicated game to engage with at times. And – mild spoilers – I really enjoyed the large timeskips in the story, which gave some space to let the characters change and grow in response to your actions. Sometimes things you thought would go badly turn out to have good side-effects, and sometimes things you thought would go well create unexpected problems, and isn’t that just the way of the world?

It feels like a good example of a game that was smart to release on Game Pass. It’s hard to imagine many players getting excited at the idea of a 16th-century murder mystery with historically-accurate politics, but it’s a lot easier to imagine Game Pass subscribers thinking that it looked weird enough to try for an evening… and then find that it’s actually surprisingly accessible, and stick with it until the end.

Shadowrun: Dragonfall

I’ve read that this second game is probably the best of the trilogy, although personally I found it a bit predictable and uninspiring. The overall design of the campaign has strong Neverwinter Nights vibes – like you know that they’ve catered to every class archetype, so most puzzles have parallel solutions using combat, stealth, hacking, or magic, if you look hard enough. I, as is my habit, went down the route of hacking and diplomacy and spent my time persuading people and computers to do what I want with minimum fuss (with a few skill points slotted into Assault Rifles, for situations where talks break down).

You’d hope that a game with such an expansive science-fantasy setting would have some weird little nooks to explore, but it comes across as quite textbook stuff. Imagine: If you were a futuristic metaverse cowboy visiting a second-hand cyberware dealer in some grimy, back alley shop, it seems unlikely that they would stock the exact same range of head computers as every other vendor in the city, at the same prices, with the same clear escalation in capabilities from model to model. That’s perfectly rational economy design for an RPG, but doesn’t fit the fantasy of the world. It doesn’t fit the reality of our actual world.

I did enjoy the story generally – it sits well in the Shadowrun mould of exploring the existential threat posed by unfettered capitalism and/or dragons. I think my complaint is that the system design is perfectly fine, but there’s not much depth and meaning to the content running through it. Thanks to your team-mates skills and abilities there are very few moments where your choices are meaningfully limited by your skills, and every branch of equipment has one short, linear upgrade path – it’s hard to feel like you’ve made good choices, because it’s very difficult to make a bad choice.

Vampire Survivors

One of the big indie hits of 2022, Vampire Survivors presents itself as a sort of casual twin-stick shooter played with only one stick. You play as a vampire hunter, and you have to survive as long as you can while being attacked by bats, zombies, mummies, ogres, wizards, and other baddies. If you’ve ever seen a screenshot of it – and you probably just did – then it most likely looks like an incomprehensible soup of sprites and damage numbers. Don’t feel put off by that! By the time the game ramps up to that stage, you’ll understand which bits of information you need to pluck from the chaos.

Vampire Survivors insists that you take it at face value at first – that this is a action game, and success comes from making good tactical decisions about moving and fighting. Once you get some upgrades and unlock more gear, it turns out that it’s really a game about buildcrafting rather than combat – success comes from making good decisions about which weapons and items to pick up, and putting together a combination which means it doesn’t matter where you move because no enemy can touch you. Eventually you loop back round to the other end of the horseshoe and suddenly it is about tactical movement again – not because you need to carefully pick your battles to stay alive, but because you need to aggressively seek out enemies as efficiently as possible, in order to put your build together faster and maximise your final score.

I found it a bit boring during the first few runs, but once I got over the initial hump and the real game revealed itself, I really fell for it. I think my biggest complaint boils down to uneven weapon balance – there were some weapons that were so much better than others that they feel almost mandatory, which hastened the moment where the game started to feel repetitive, but only after many hours of fun trying to set up particular over-the-top build ideas.

I don’t find the core gameplay very satisfying, but I did come to appreciate the scope of the metagame – there’s a huge number of characters, weapons and abilities to unlock, and there’s a satisfying tangle of overlapping trigger conditions to unlock them. You’re given reasons to try everything out sooner or later, pushing your build blueprint in every available direction; you’ll probably find yourself settling into a rut eventually, but it does a good job of nudging you to explore the possibilities and find the fun in other builds. I think there’s a lot to learn from this aspect of the game, at least.

Arcade Paradise

I was drawn to Arcade Paradise in part because I knew it was made by Nosebleed Interactive, and I become filled with patriotic fervor when games are made in Tyneside that don’t involve cars.

You play as a teenage slacker in the early 90’s who nepotistically falls into a job managing your dad’s old launderette, and then slowly – piece by piece – convert it into an greasy, smoke-filled, neon-lit arcade without him noticing. It’s a ‘job simulator’ sort of game – you scamper around picking up trash, putting clothes in to be washed and dried, fixing defective arcade machines, and so on – although as the game goes on the emphasis shifts away from this kind of menial work, and towards simply playing the arcade games.

I think I was hoping this game to feel more like an arcade than it actually did? As the game progresses and you fill out your back rooms with a diverse mix of cabinets, there is a nostalgically chaotic atmosphere – the sound of overlapping attract mode jingles washing over you from every direction. But while you do get to play the games, there’s something a bit sad and lonely about the way your customers behave like ghosts. You could look at a screenshot above and think that it has the atmosphere of the 90’s arcade in the middle of the week, but when you move close to any of the customers in your arcade they fizzle out of view. They’re just a visualisation, and while there are some moments where characters will email you to feud over high score table positions, it mostly felt like I was in some sort of Doctor Who episode, trapped in an ancient arcade filled with ghosts of teenagers from a dead planet. There are a lot of very understandable technical advantages to doing this, but I feel like it rips a lot of life out of what should be a very social space.

Each game in the arcade has a set of upgrades that are locked behind gameplay challenges, and over time it starts to feel a bit like Wario Ware or Clubhouse Games – a feeling that you’ve tunneled down through the bedrock of the business sim aspect of the game, and broken into a cavernous anthology of arcade minigames. The arcade games themselves are often fun, and often seem inspired by particular real-life games, which adds to the humour.

It was fun. Also it’s getting a VR port at some point.

Pikmin 3

The Pikmin games are a sort of realtime strategy / management sim / action-RPG hybrid. They all follow a roughly similar narrative setup – a tiny spaceman (or a group of tiny spacepeople) have crash-landed on a mysterious alien planet; in order to escape, they need to explore hostile environments filled with dangerous beasts, and recover resources that are many times too big and heavy for them to move on their own. Fortunately, they encounter the Pikmin – a strange species of highly suggestable plant-people who can be grown from seed and taught to perform manual tasks (such as attacking monsters, or carrying large objects). By expanding and commanding their army of Pikmin, the marooned spacepeople pacify the native threats, build infrastructure to help traverse the wilderness, and extract lots of valuable materials with which to repair their ship and return to their home planet.

Pikmin 4 came out this summer, which reminded me that I had a game of Pikmin 3 on my Wii U saved just before the first big boss (shown above). I decided that rather than buying another full price Switch game this year, I’d go back and pick this up again and get my fill of Pikmin for free. I never played Pikmin 2 and the original Pikmin was one of the games I bought with my GameCube, so it’s been about two decades since I last really cracked into one of these. What did I learn?

Pikmin always stuck out in my mind as a game where you were constantly running against the clock. Every level plays out over the course of a single ‘day’ with a fixed duration, but the more challenging aspect was that you had a limit of 30 days to complete the game – if you spent too much time dawdling, or completed a long puzzle only to find you didn’t have enough Pikmin with you to carry the prize back to base, there was a risk that you might fully lose the game and have to start from the beginning again. It’s brutal stuff.

In Pikmin 3, one of the big changes is that your final deadline is more of a rolling counter. You are judged by how many bottles of fruit juice you have left for your crew to survive on, and this number does tick down by 1 after every mission, but (unlike the original game) you can also increase it again by bringing home more fruit. It felt satisfyingly tense during the first few levels, but once I got deeper into the game and started hauling back industrial quantities of fresh produce, the time economy seemed to blow through the roof – by the end of the game, I think I had about 50 days worth of juice left in the tank. It reminds me of the Dead Rising sequels – the way the game was changed to be more forgiving and accessible to new players, and in doing so killed the unique atmosphere that made the original so memorable.

I enjoyed it, but it felt quite easy to get into a position where the game held little challenge, and without that pressure on my shoulders it started to feel like a box-ticking exercise. I got back into the old routine of spending one day pacifying enemies and opening up shortcuts across the map, and then using my second (and sometimes a third) day to hoover up all the fruit and items. It just didn’t feel like a problem – aside from the boss fights, which always put an interesting twist on things, I often felt like I was just going through the motions.

Destiny 2: Lightfall

I didn’t care much for Lightfall.

The overall setting of Destiny has always been one where you’re picking through the ruins of an ancient civilisation – the ‘golden age’ of an Earth long past, with you playing a sort of zombie space marine brought back from the dead to help fend off an overwhelming tide of alien invaders looking to snuff out the last embers of mankind. In Lightfall we are told that – oh! – there’s actually a hidden pocket of golden age society who have been living in a city on Neptune for hundreds of years that everyone has simply failed to notice. Until now!

As locations go, Neomuna (as it is known) is an interesting, visually distinct environment – a very vaporwave inspired world of smooth curves, neon pink lighting, and holograms. It does make a change from the usual format of broken-down buildings that have been reclaimed by the forest / the dunes / the sea (delete as appropriate). But the story that plays out there just sounds weird and out of step with the previous expansions, and even if you accept that and move on it still raises a lot of questions. Neomuna is supposed to be a living city, home to thousands (?) of people, but – oh! – they spend literally all their time jacked into cyberspace while their bodies are tucked away in cryogenic suspension, so you never actually meet any of them in person (unless you count the abstract wisps of their virtual selves, floating around in the city streets). It feels just as dead and deserted as every other planet you visit, except that there’s constant radio chatter from the cyber-ghosts of the city’s residents who seem content to sit back and watch you defend their city through their security cameras, occasionally pausing to record a podcast about your progress. Why am I supposed to have any sympathy for these people? We should be stripping this place for parts and taking it back to Earth.

It’s a shame because one of the best moments in Destiny 2 was that final mission in the original campaign where you go down into the Last City and scour the streets clean of alien invaders. It’s a place you see a lot of, from a distance – as a sweeping, background landscape you look down upon from your social hub – and it felt very meaningful to finally go down there and see how the last embers of mankind were actually living. It was the moment you stopped being a distant, detached superhero looking down from an ivory tower and (…almost…. sort of….) rubbed shoulders with the ordinary humans you were supposed to be defending. Except of course, you never actually saw any of them because they had either been evacuated or killed already. But still, it was a thing! It came very close to being a thing.

They had an opportunity here to take the player to an actual living city and inject some fresh character into the game, but… I mean, maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that they didn’t introduce a load of walking, talking NPCs into a game that was never really designed for that sort of thing, but if they weren’t going to do that then why pursue this idea for a location at all? As an outsider it would be foolish to speculate about what kind of decisions were made and what kind of constraints they were up against, but all I can say is that the final result seems odd to me.

I remember when Destiny was announced, it was described as being the start of a ten year project for Bungie. A lot has changed in the last ten years, and I doubt the original plan has survived unscathed, but it does seem fair to think that The Final Shape may end up marking the end of the series, or at least that they might make a hard break from Destiny 2 with a full sequel.

Advance Wars 1+2: Re-Boot Camp

I’ve written a few things about remakes of old strategy games (see: Command & Conquer, Age of Empires) and one of the big things on my mind is where they stand on reproducing the original games’ weird AI behaviours. I can report that the Advance Wars AI is still singularly obsessed with killing APCs and transport helicopters, although this is one game where I feel like it might have been better if they fixed that.

Advance Wars is about 20 years old now and is available on lots of different hardware platforms (particularly if you turn to piracy, or Advance Wars By Web). I don’t want to spend a lot of time talking about how much I love it, but it’s just a really good turn-based strategy game with a very tight roster of units, and a set of characters that inject fun twists into the gameplay with their unique abilities. Could it be better? Yeah, sure; but you can look at a game like Wargroove to appreciate how hard it is to get the balance as good as it is. Two decades on, Advance Wars is still my go-to reference point for what a fun strategy game should be like.

The real question I want to grapple with here is how this remake stands up next to the original, and the short answer is that it’s extremely faithful to the gameplay while nudging the game’s visual style in a slightly new direction. The battlefield is presented as something like a wooden board game, while your dinky tanks and soldiers are now rendered as 3D models rather than icons. I do feel like the changes take something away from the game – the soldiers in particular look like smooth, CGI Morph-like characters, rather than the SD anime style of the original.

After spending a year playing AWBW, I’ve come to think that Advance Wars suffers from a lot of the common struggles of trying to link the game’s economy to the state of the battlefield. The real nub of the game is about capturing (or simply parking units on top of) enemy factories, and it can be a bit of a grind when you’re trying to do this on a symmetrical map, where the one big tie-breaking factor is which character you chose to lead your army. There are limits to how many multiplayer games I can stomach, but I do think the single-player campaign – which (like most strategy games) is really more about solving unique problems with a toolkit of given units – is still extremely replayable. The biggest thing holding me back is my obsession with getting perfect scores on every level.

Teardown

I followed this game’s development through gifs on Twitter for years before it came out, and was very happy to finally play it this year. Its key feature is its detailed, complicated destruction physics system – you can smash windows, drive vehicles through walls, set fire to things, and the resulting damage is modelled out in a much more granular and realistic way than in most games. It’s a little bit like playing a smaller-scale, higher-fidelity Minecraft. There is a single-player campaign in which you play as a sort of private security expert who takes on jobs to break into places and test alarm systems, but that’s kind of an afterthought – a narrative tissue wrapped over this chaotic sandbox where you get to smash holes in walls and generally redesign the geography of a space to suit your objectives.

It’s good fun – like being 3 years old and knocking down a tower made of wooden blocks, except there’s no need to tidy up afterwards – although I’m absolutely aching for the deformation tech to be reworked into an Earth Defence Force style horde shooting game.

Marvel Snap

I played this quite heavily for a few months and thought it was – similar to Clash Royale – a great example of how to tailor a genre to suit the mobile market, but I also never felt like I had anything to gain by putting money into it. The card unlock progression felt very linear, and most of the decks I played against seemed to follow a handful of common build archetypes, which made the game feel repetitive and impersonal – people often seemed to play their decks AT each other, without a lot of interaction and response to one another. It was fun to play out, but I would reach the end of most matches thinking “What was the point of this?”

With that in mind, I made a deck that was specifically designed to interrupt and undermine the most common combos I was coming up against. I still lost quite often, but it make the game much more interesting – it’s a deck that requires you to study your opponents’ moves, predict their upcoming plays, and set up counters and combo-breakers to land just at the right moment. If you want to give it a go, try the following:

Elektra – Nightcrawler – Lizard – Scorpion – Scarlet Witch – Carnage

Armor – Killmonger – Shadow King – Shang-Chi – Enchantress – Hobgoblin

My biggest piece of advice is that most of these cards (with the exception of Scorpion, and usually Nightcrawler) have a greater impact the later they are played. Don’t be afraid to skip a couple of the early turns if you think you might need one of your cards later – playing Elektra on the final turn became one of my most common moves, as a cheap way to bump off a heavily buffed Sunspot or Nebula, clear a landing zone for Hobgoblin, remove Lizard’s debuff, give Carnage a little extra food, steal control of the Mojoverse, and other tricks.

Later I watched a Twitch streamer reach rank 100 using a Negative Surfer deck, and I noticed that I already had all but one of the cards required, so I copied that and enjoyed huge success for months without having to think for myself at all. I think that’s been my main lesson about the current state of Marvel Snap – I found my own deck much more interesting to play because I had to study my opponent’s moves and predict when and where to drop my counterplays, but it was much more effective to simply bulldoze my opponent with a ridiculous combo on the final turn. The raw power of simply playing that deck AT my opponent – of dropping that deck onto their head like a piano in a Road Runner cartoon – made my deck of interesting counterplays feel self-indulgent.

Looking back now after six months, they’ve added a number of cards that make these final turn supercombos harder (Alioth being a prime example) and I think the meta has adapted to counter this deck’s popularity (I’m seeing Cosmo and Leech a lot more than I used to). But mainly I just keep thinking… I had a lot more fun playing with my self-indulgent, low-scoring counterplay deck. That was a more fun game to play! But it’s not what this game is, right? Am I done with it? Maybe I’m done.

I think Marvel Snap‘s best innovation is the Snap and Retreat mechanics – the way that either player can raise the stakes during a match (with a Snap), but can also cu their losses by Retreating. Judging when to Snap or Retreat adds a lot to the social mindgames taking place during a match, which helps to balance out the card meta a little – eg. it’s only really in each players’ interests to ride a match out to its conclusion if they think they have a chance of winning, so there’s a certain metagame advantage in using a deck (like Negative Surfer) that appears weak right up until the end… but it comes with the risk that your opponent might find a way to block your winning final play. It’s a clever design, and it does a lot to elevate the game beyond just playing the same cards at each other over and over. More games should copy this idea!

The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

It feels inevitable that this game is going to get judged in relation to Breath of the Wild – particularly since they take place in the same world, featuring many of the same characters and locations and powers and things. I’m not sure if I’d compare their relationship to Majora’s Mask and Ocarina of Time – I think Tears of the Kingdom is too conservative in its ambition for that to really hold up – but there is some sense of that in here… the idea that the developers were going to take what they made before and play around with it a little, to see what they can make with a bit more time and freedom. So, I’m viewing it as a sort of semi-sequel – not something that should be regarded as a fully original follow-up, but more like a re-imagining that might breathe new life into the previous game.

The old powers and mechanics are more-or-less present, although they’ve usually changed and evolved in some ways. The real standout part of the new content is the Ultrahand ability and the Zonai devices – being able to glue together some planks of wood and mechanical components to build your own weird little machines. I do think that the game becomes a bit trivially easy when you can press a few buttons and summon your own little jet-powered glider, but I feel like it’s fine really – it opens up a lot of scope for freeform play within the world, which is a smart decision when we’re returning to a map that we’ve already been playing on for years.

One of my favourite elements of the game was the new house-building feature. I put quite a bit of effort into building a luxurious three-storey home with a garden balcony overlooking the nearby town, and I liked having my own in-house facilities for spending orbs and stabling my horse and so on, but I did get a bit frustrated with how rigid the architecture felt. Each room is (generally speaking) a box with one missing wall, but there’s no option to add walls or doors between the rooms. This is one relatively unimportant feature within a game that’s packed full of ideas, but it bothered me because I enjoyed where the concept was going so much.

The thing I find weird about Tears of the Kingdom is that The Depths clearly follows in the tradition of mirror worlds in Zelda games – think of the Light and Dark worlds in Link to the Past, the two time periods you could move between in Ocarina of Time, Hyrule and Lorule in A Link Between Worlds, and so on, and so on… but…. once you tap into this and start to understand what its whole deal is, The Depths feels weirdly empty compared to Hyrule. Why isn’t there a stockade of ghostly Hylian soldiers keeping watch beneath the royal crypts or something? Or a town full of Gorons, or some weird new race who just happen to live underground? I mapped out the whole of the Depths, and it’s like an abandoned basement car park full of optional boss fights, and two or three unique locations that you visit to advance the plot. It’s big, and there is stuff down there, but it’s much more limited in its range of experiences than the overworld, and I felt like that undermined the concept.

It’s not just about the size and emptiness of it all, but… another one of the key things in this game is the image of Princess Zelda as a historian, right? The opening cutscene shows her doing archeological research and translating ancient glyphs. I feel like The Depths should have started as this scary, dark underworld zone that you dip into for resources (but probably shouldn’t spend too much time in)… but there should be a gradual shift towards exploring ancient ruins in The Depths to bring back forgotten knowledge and technology to turn the tide in your battle against Ganon… which admittedly is exactly what happens, eventually, but it happens one time only. It feels weird to me, considering how many colosseums and optional boss rematches and the like down there offering relatively conventional rewards. There was an opportunity here to have the player follow in Zelda’s footsteps and do their own research and exploration, searching for ways to learn from Hyrule’s past, but to the extent it happens, it all takes place in a few Main Quest objectives, and that doesn’t feel very exploratory to me.

With these criticisms in mind, I must award Tears of the Kingdom a low 10 out of 10.

Command & Conquer: Remastered

I played through the NOD campaign in Command & Conquer and the Soviet campaign in Red Alert, as part of a push to finish more games and clear up my ‘installed games’ list on Steam. I also got halfway through the Allies campaign, before I hit a wall and got sick of restarting the same mission over and over.

I’ve already talked about the game at length on more than one occasion, and I won’t repeat myself here. But – not as a criticism of this game specifically, but more like a reflection on what RTS campaign design was like was like in the 90’s – I get very tired of all the free, scripted, off-map reinforcements that the enemies get. This isn’t just about the Allied mission I gave up on – I remember in the Soviet campaign, one big slice of the success pie always came from locating where the enemy’s free reinforcements would arrive from, and then hardening the area with Tesla Coils and SAM Sites and walls to put them down as soon as they appear. Once your CPU opponent is forced into a ‘fair’ fight, it usually means you have a huge advantage over them.

In a weird way, I actually think it’s better to have reinforcements coming in waves from the edge of the map, as in World in Conflict. But the problem here is that Command & Conquer isn’t designed around that sort of system, and the player has no sense of what to expect – there’s no way to know that you’re about to receive some free units, or how long you have before another enemy transport full of tanks and artillery will spawn in. If I could save up reinforcement units and select when and where to bring them in, like in Age of Empires III… or see some clear objectives that tell me when the enemy waves are going to spawn, and what I need to do to cut that supply line… that would be nice.

If memory serves, they did a better job of this in Red Alert 2 , in the way they laid out optional secondary objectives – clear, actionable goals with some description of what the impact would be (eg. “Destroy these two secondary radar bases to hinder the enemy’s ability to call in airstrikes”). And so we enter our fourth year of quietly hoping for Command & Conquer: Remastered, Volume II.

Umurangi Generation

I have a long-held lowkey interest in photography games – games that can combine the same sort of physical skills as a shooting game, but with less immediate danger and more focus on planning and preparing for each shot (mmm, delicious planning…)

Umurangi Generation is a game in which you play a photojournalist living through an alien invasion. Each level drops you into a small environment with a list of vaguely-described objectives – particular images you should capture with your camera – and it’s up to you to choose some appropriate camera settings and find the right place to shoot from. Often this means lining up two or three different subjects in one shot – the means by which the game pushes you to reach particular positions, or use particular lenses.

The environments are chaotic, colourful spaces where hip teens have congregated to witness the end of the world. It was somewhere in this area of the game where it started to lose me – the choice of locations are interesting, but the action taking place within them felt very static to me. I want to walk around and poke at things and talk to people a little… I want to trigger little scenes to capture specific moments, like in Pokémon Snap. Also, the general visual design just felt a bit too intense for me at times. If you look at the little screenshot above, levels like this had so much information and design fighting for my attention, I struggled to understand what my objective clues were supposed to be pointing towards.

I generally choose games to play based on whether they look like something I would enjoy, which is why I often come away writing positive reviews… so it feels a little weird to write about a game and then conclude that I didn’t enjoy it much… but here we are I guess.

The Movies

The Movies is a classic management sim from Lionhead – a sort of distant descendant of Theme Hospital, but with a narrower focus on its more expressive, Sims-like characters. I think it was the last game they made before they were acquired by Microsoft and pivoted to focusing on the Fable series. If you’re a fan of Bullfrog’s management sims, this is kind of a significant entry in the timeline! I bought this game when it came out and played it for some time, but never finished it. So I sat down one morning and decided to give it another go and see where it led me.

The game is about running a Hollywood movie studio, from the 1920’s through to the modern day. You build sets and studio facilities, hire actors, directors and other crewmembers, and trying to make sure everyone feels happy and creative while pumping out films on time and on-budget. Your ultimate goal is to produce feature films, but – as is typical for Peter Molyneux’s sim games – you control this process indirectly by manipulating a group of little computer people who have their own goals, flaws, and emotions. You may find that one of your actors becomes jealous of one of their co-workers, because they have a larger caravan on the lot; a director might feel overworked from the relentless shooting schedule, turn to the studio bar for some refreshment, and develop an alcohol problem. You might put out an imaginative and beautiful film, only for it to flop on release because audiences are sick of these particular stars making another one of these movies, year after year. You need to manage the physical and emotional needs of your workers in order to maintain a smooth production pipeline.

It’s got a lot of great stuff going on in it, but I also think there are some shortcomings that make it hard to love. It’s hard to understand what audiences want, and it’s not always clear that it really matters whether you know or not; it’s difficult to get stars to de-stress between films, unless you actively micro-manage them through long, casual hang-outs with other stars. I played through a complete run of the game this time, and after a certain point the game just sort of… stops; there’s a pop-up saying that you have reached the modern day and there will be no new unlocks to come, but you can continue cranking out movies if you want to.

One of its weird and interesting features is that the movies you make can be exported as actual movies and watched outside of the game – if you search YouTube, you’ll find lots of short films made in the game. It’s a really fun idea – you have a lot of control over the scripted scenes and the action within the game. You can visit the script office to modify the script, visit the set during filming to fine-tune the actors’ performances, or even build a post-production office to record your own dialogue or fiddle with special effects. If you’re interested in making weird little machinima films, I’d say it’s worth playing just for the sake of noodling around with these tools. I’m surprised it haven’t found more of an audience with modern content creators – using it to knock together weird little memes, or to “prove” that the latest Marvel movie should have had a different ending – but I guess coming out in 2006 meant the game was slightly ahead of its time in that respect.

Like most Lionhead games (with the exception of the Fable series) I don’t think this is for sale anywhere these days. There is a demo available online which might still work on your system, and if you can find a disc copy of the game then there are various unofficial mods you can install to support modern hardware and quality-of-life standards, but do please be careful not to accidentally download a pirate copy of this otherwise totally unavailable game.

Persona 5 Royal

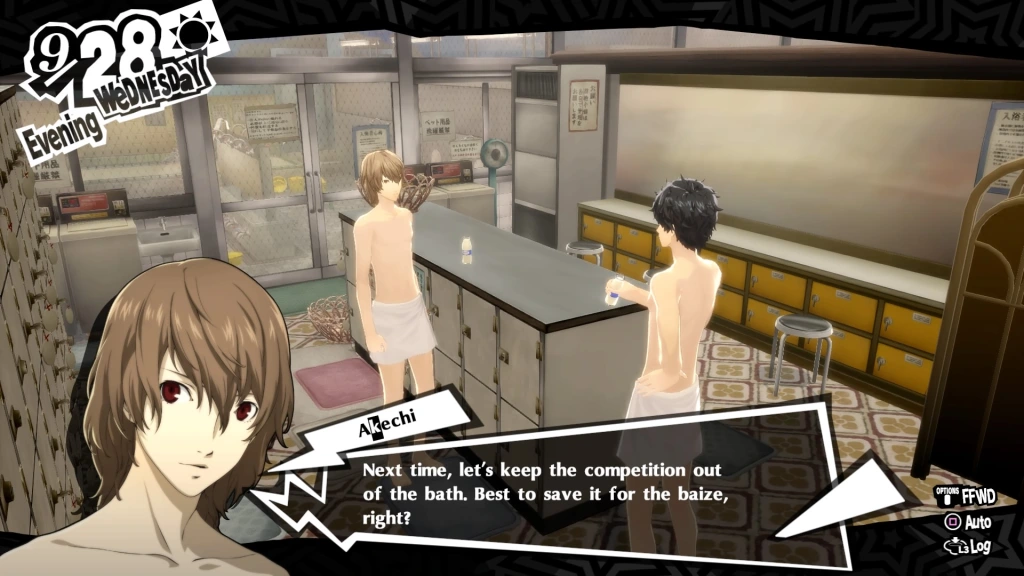

I said last year that I was thinking about trying Persona 4. I ended up playing Persona 5 instead, after talking to a colleague at work who was particularly effusive about it. It was good!

It’s an RPG in which you play as a group of modern day spikey-haired teenagers who gain the mysterious ability to slip inside people’s minds and explore their inner emotional perception of the world. The gang use this ability to break into the minds of evil-doers, destroy their twisted self-image through the turn-based application of guns, baseball bats and magic spells, and render them so mortified at their own behaviour that they publicly confess to whatever it is they’ve been doing and vow to lead a more honest life in future. Or that’s the plan, at least.

It follows a similar format to the previous Persona games – the game plays out over a fixed calendar period, and you must make choices each day regarding how you will spend your time. I feel like there was much less emphasis on grinding dungeons to improve your character stats than in Persona 3, although it’s possible that I was just playing the game differently this time. The result was that this felt much more like the kind of Persona experience that people keep telling me about – there’s something quite relaxing, and almost Stardew Valley-like about delving into the random battle labyrinth to work on side-quests one evening, and then meeting up with a friend to eat burgers and go to the cinema the next. I also need to give some mention to how much I enjoyed its sumptuous depiction of Tokyo! It doesn’t match Yakuza‘s granular detail, but it covers a much broader range of locations around the city – easily the second-best depiction of Ogikubo in videogames, after Earth Defence Force.

I enjoyed the story a lot – a sort of dark psychodrama about teenagers dealing with trauma and abuse and simmering sexual energy (but with jokes). There’s something about the concept of diving into people’s minds that makes teenage protagonists feel like a perfect fit. The party have a certain level of arrogance to them – while they each have one core emotional trauma in their backstory to form the base of their character arc, they’re also young and inexperienced enough to have this absolute conviction that it’s Good and Cool to shatter people’s minds and tell them how to live. There’s something about the undercurrent of surging pubescent hormones that makes the weird sexual imagery of some of the game’s Personas (who are basically like… guardian spirits formed from aspects of the characters’ inner psyches) make perfect sense. It’s a series that sometimes gets criticism for its unreformed depiction of bodies and gender identities, and I do think there are valid arguments for this, but at the same time I think it’s true to the nature of the teenage mind that some of the characters have a deep ignorance and/or singular fascination with sex.

Persona 5 Royal is, specifically, a sort of ‘complete’ edition of the game with some added expansion content – an additional chapter of the game, if you fulfil certain conditions during the main story arc. I think this is where I’d put most of my criticism – the expansion content makes for a much better ending to the story (for reasons that I don’t want to explain here) but there’s something about the way that it’s been integrated into the game that feels unsatisfying to me. Something about how certain characters’ social links are capped at lower levels, for reasons which aren’t particularly explained, stuck out in my mind… or maybe it’s about how the new final chapter feels like a hidden true ending, but it’s also an expansion pack? It’s entirely possible that you’ll buy it but not know how to unlock it and miss it? I don’t know.

Oh, I also think it would have been good if [a certain antagonist] had used their power to dive into the main character’s mind and try to change their outlook on life from under your nose, but I’ve been reliably informed that Persona-wielders don’t have the kind of intrudable inner worlds that normal people have, so I GUESS THAT’S THAT.

Wonder Project J

Another fan-translated SNES game, Wonder Project J: Kikai no Shonen Pino (to give it it’s full title) is a sort of Tezuka-like sci-fi spin on the Pinocchio story. I would attempt to describe the gameplay as a cross between a Princess Maker sim and a point-and-click adventure – you can’t really interact with the world directly, but you can teach a robotic goofus called Pino to do the needful on your behalf. Draw his attention to a book and he might try to read it, eat it, throw it, or jump on top of it and sing a song, depending on the state of his personality stats. You must praise and punish him for his actions to slowly teach him how to behave, and shape his behaviour to fit the puzzles placed before you. You might even say it’s a puzzle-based forerunner of Black & White?

The game is structured in a series of chapters. Each chapter starts with a short animated title sequence, ends with a particular puzzle that young Pino must overcome, and is filled in the middle with you moving around the island and finding the right combination of items to interact with to grind his stats into the kind of balance that might solve the puzzle. The thing I found most interesting was that some stats – especially the more psychological ones – had particular benefits right across their range of values. For example, Kindness is important for the more social-oriented puzzles but can become a barrier in the combat-oriented puzzles, if Pino feels too compassionate to fight. You can’t beat the levels by simply maximising your stats – you have to nudge everything up and down to strike a particular balance.

I started playing this because Lies of P had just come out and it felt like an appropriate moment to play a weird Pinocchio-themed game. Everyone keeps telling me that Lies of P is a lot like Bloodborne and all I can tell you is that Wonder Project J is nothing like Bloodborne at all.

Two Point Campus

I enjoyed Two Point Hospital, but when I saw the first trailer for Two Point Campus I had lower expectations for it. The new setting didn’t feel like a clear fit for the genre.

In Hospital – and in Theme Park, for that matter – you are trying to manage a steady flow of ‘customers’ who are coming into your facility, spending a bit of time there, and then leaving when certain conditions are met (eg. being cured, dying, running out of money, etc). I think what bothered me about the idea of university management was that students come and go on a very particular kind of schedule – there’s no stream of new arrivals, just a single big bucket of freshmen being dumped into the pond at the start of each year. I furrowed my brow and supposed that it just wouldn’t be the same, and I was right.

The way to structure your facility in Two Point Hospital was to think of it like a conveyer belt. Success comes from laying out your specialist rooms intelligently, to minimise the amount of time patients and staff spent walking from place to place – eg. concentrating your generic diagnostic rooms in a big building near the centre of the map, and then becoming more specific and more treatment-focused as you move out from there. If you minimise travel time then patients will be cured faster, the hospital will be less congested, it will be a more sanitary environment for the patients who remain, everyone will feel happier, and so on.

With fixed term lengths this whole approach is thrown straight in the bin, but before you can say “Confusing metaphor” it bursts back out in a new configuration, like a butterfly exploding from a cocoon. Two Point Campus is about maximising the quality of your output, rather than minimising the time it takes to produce. Students will spend a fixed amount of time on your campus, and your primary goal is to cram as much knowledge into their brain as possible within that time limit. It turns out this is a very similar problem, but requires you to think about it from a slightly different perspective.

The result is that I still structure Two Point Campus like a series of concentric rings, but instead of starting at the center and slowing migrating out to the edge, my students transition back and forth between layers. I put the important, generic learning rooms (like the library and the lecture theatres) at the center of the map, surrounded by a layer of subject-specific rooms, and then entertainment and dormitories on the outer edge, with toilets and snack machines present in every building so nobody has to go out of their way to fulfil their basic needs. The student body, as a general mass, start on the outside edge as they move into their dorms, and then spend most of the year moving between the central core and the middle layer of subject rooms – coming together and breaking apart on these regular monthly schedules, as if the campus is a giant set of lungs breathing in and out.

Does any of this really help? I’m not sure. But I sure did feel pleased with myself for making up that visual image. I enjoyed this game a lot more than I expected to, and there’s a Medical School expansion out which (I assume?!) asks you to blend some Two Point Hospital logic back into the mix, which sounds like another fun twist.

Station to Station

I saw a trailer for this during the summer and thought it looked lovely, so I bought it. That’s how it’s done.

Station to Station is a puzzle game about connecting nodes on a map, on a budget. Each level comes with a particular set of resources in particular locations – a wheat farm here, a windmill there, a bakery on top of the hill – and the puzzle element lies in how you choose to connect these nodes, and in what order. If you turn your head to the right angle it’s a sort of distant cousin of The Settlers. Most of the game is about placing railway stations and tracks, but there’s a little extra texture to play with in the form of bridges and junctions and special effect cards that can make a huge difference to your score if played at the right time.

I got about halfway through this game while clearing all the special objectives for each level (reach a certain high score, score a single massive combo, don’t build any bridges; these sorts of things) and then reached a point where I could still finish each level easily enough, but I couldn’t quite beat all of the special objectives. It’s a little silly, but I’d built up such a long run of ‘perfect’ solutions that I felt compelled to keep restarting each level until I had cracked it, and after a while I just got sick of staring at the same levels over and over. There is some amount of being able to undo moves and reload previous level states, but in most cases I found myself having to start the whole level again.

I still think it’s a really beautiful game, but even without my niggling perfectionism I found the puzzle gameplay a bit repetitive. You earn big combo bonuses by connecting certain combinations of nodes, so the basic recipe for a high score is to connect up all your primary and tertiary industry nodes (eg. wheat farms and bakeries) on one network, and all your secondary industry nodes (eg. windmills) on a separate network, and then connect the two networks as your final move.

I think it would be good if the levels felt less prescriptive. The type and position and order of appearance of each node is preset so the puzzle design can be kept tight, but I think the general look and feel of the game is such that I’d like more scope for personal expression. Maybe I’m just asking for a different kind of game here? Something a bit more like A-Train, but with levels that are small enough to complete in 10 minutes… less puzzle-y and more like a slimmed-down management game. But I liked the direction this game was heading in, even if I didn’t entirely love where it is right now.

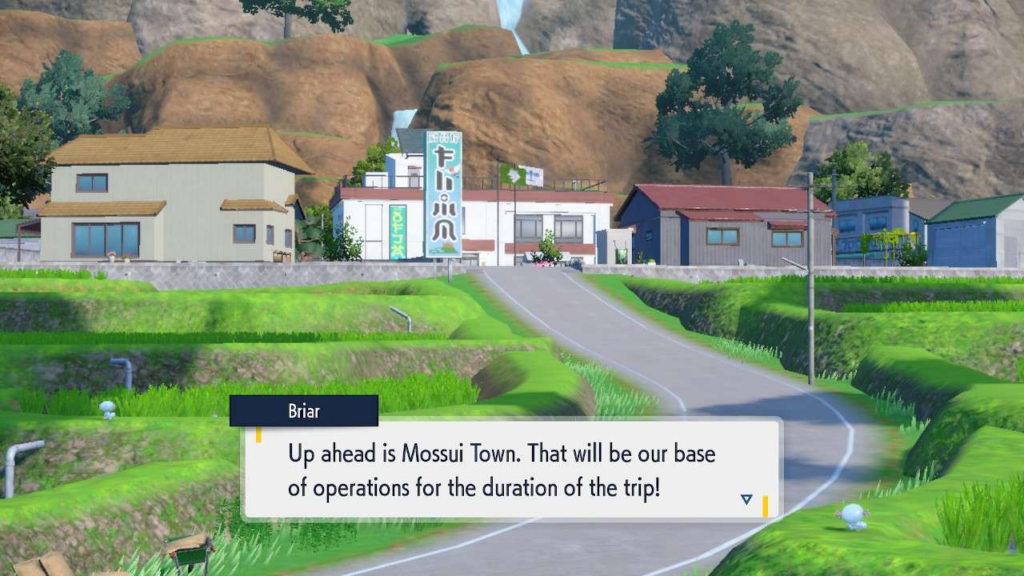

Pokémon Violet – The Hidden Treasure of Area Zero (DLC)

I played both parts of this DLC pack (The Teal Mask and The Indigo Disc) when they came out, and they both felt quite tenuously connected to the main game. They added many (but not all) previously-absent Pokémon, which feels like the main thing fans were looking for, but I don’t feel like they added much texture to the setting of Paldea.

In The Teal Mask you are invited to join a school trip to (the Pokémon world’s equivalent of) rural Japan, where you get caught up in some longstanding small-town beef. According to the local legends, the town was terrorised centuries back by a big, bad Pokémon who lived in the nearby mountains, but was saved by three other Pokémon who banded together to drive the bad guy off. You have arrived just in time for the annual festival where the locals celebrate this event and pay tribute to the heroic Pokémon who saved the town. However, there is one family who insist that the local legends are wrong – that the ‘bad’ Pokémon was actually a really sweet guy, and the ‘heroes’ stole his things and bullied him out of town. This is a cultural schism that has divided the town for centuries, and now it falls to some 10-year-old exchange student to spend their school holiday putting the matter to rest.

In The Indigo Disc, you are chosen to go on another school trip, this time as an exchange student to… how do I put this?…. It’s basically a high school, right? But whereas your home school is a sort of towering Pokémon Hogwarts that sits at the center of the map, the school you’re visiting is a remote offshore facility that sits above an enormous underwater bio-dome maintaining four distinct climate zones full of Pokémon. The teenagers who are enrolled at this school sleep in underwater dorms, attend classes in underwater study rooms, and when they’re ready for field work they ride an elevator hundreds of meters below sea level to visit their own private safari park and learn how to catch a Pidgey. WHO IS PAYING FOR ALL THIS?! WHY ARE THEY SPENDING (presumably) BILLIONS OF POKÉMON-EUROS TO TEACH KIDS BASIC POKÉMON TRAINING SKILLS, WHEN EVERY OTHER COUNTRY ON POKÉMON-EARTH IS CONTENT TO JUST KICK THEIR KIDS OUT OF THE HOUSE ON THEIR 10TH BIRTHDAY AND GET A FREE EDUCATION FROM PASSING STRANGERS? What an insane waste. Paldea seems like an absolute clown country.

Anyway, are they good? Not particularly. My favourite part of the whole thing was the initial approach to Mossui town at the start of The Teal Mask, which you can see for free in the screenshot above. It was like a nice little virtual summer holiday, to a side of Japan that you’re not likely to see in a Yakuza game.

Rather than listing off my complaints, I’ll just reiterate that I think Pokémon Scarlet / Violet is a good sort of direction for the series to be heading in, I just think it’s weird that Pokémon games aren’t afforded the same level of polish that a first-party Nintendo game would be. This is one of the biggest game franchises in the world, and the mainline Pokémon games deserve to be unquestionably good games – big, paragon, flagship titles that will leave kids wondering why people even bother to make other games. They shouldn’t be indicating the direction of the series; they should be the destination.

Final Fantasy XIV: Post-Endwalker Patches

The only thing I remember about any of this was weighing up how much money I was willing to spend in the marketplace to upgrade my gear, considering it will have all tumbled down in price once the final patch comes out.

The next expansion – Dawntrail – is due out in a few months, and will introduce a new character class that uses all the same stats and equipment as my trusty Ninja, but seems to have some Monster Hunter style mode switches to it. I look forward to trying this out, eventually.

Pikmin 4

If you’ve been diligently reading down this list so far, you’ll remember that I played through Pikmin 3 as a way of getting a little Pikmin fix without having to buy the new Pikmin 4. So imagine the size of the egg on my face when I saw a really good offer on the game a few months after launch, and bought a copy anyway.

In some ways Pikmin 4 feels like a soft reboot of the series – the story feels like an alternate version of the original game, and I didn’t notice anything explicitly tying back to previous events (although the incidental text includes a lot of references to people and things we are familiar with). The plot focuses on an interplanetary rescue team, who crash their spaceship while trying to respond to an SOS signal. The crew, who are all about two inches tall, start to explore the planet and discover the Pikmin – a race of tiny plant-people who will follow you around and can be tasked to perform simple commands like a private army of ants. With the help of the Pikmin you slowly but surely repair your ship, explore the planet, and eventually complete your mission (as per every other game in the series).

So, what’s new? The main new feature is Oatchi, a rescue dog with the size and personality of a tennis ball. Oatchi can be assigned tasks such as gathering Pikmin, defending an area from enemies, or transporting objects, and you can directly control him as a sort of second character (similar to the way you can switch between characters in Pikmin 3). You can also jump on Oatchi’s back to ride around the level quickly, as well as jumping (wow!) and swimming (cor!) to overcome traditional hazards. What’s more, your Pikmin will cling to his flanks alongside you, which opens up a neat new layer of strategic planning – depending on what you need to do, you can either split up and tackle two areas of the level simultaneously, or join forces to open up more traversal and combat options.

There’s a very strong focus on the concept of ‘dandori’ – apparently a Japanese word that basically refers to efficient planning – the sense of optimising your actions within a given timeframe, in order to maximise your productivity. This is something that really gets to the heart of what Pikmin games are about, and lends a certain perspective to many other strategy and management games. I’ve read in interviews that the developers only really latched onto this focus during the development of Pikmin 3, and I like stories about people making creative things and then only really coming to understand what they were making in hindsight. In Pikmin 4 they lean right into the word, and have lots of fenced-off challenge minigames where you must complete small-scale Pikmin levels in a single two-minute run, without having access to your usual stocks of Pikmin and support items.

My biggest complaints about the game come from some of the changes which seem intended to make the game more accessible. There’s no overarching time pressure in this game – no risk of running out of oxygen, or food – so you can keep replaying levels as many times as you like, which removes the pressure of trying to squeeze all you can out of each day.

The worst thing is that enemies no longer respawn. I think this is a terrible decision! I can imagine an argument that players might get frustrated if they spend time clearing out all the threats on a level and then come back a few days later to find that the enemies have returned, but by not respawning enemies it means every level slowly becomes dead and lifeless, which feels so opposed to the spirit of the game. It seems deeply weird and illogical to me to make a game about gardening that makes you feel like you’re just strip-mining all the useful resources out of a level and rendering it an empty wasteland. Enemies should respawn, yes… but also, the player should be planting and tending to seedlings, to grow specialist plants that solve environmental puzzles. Pikmin should follow some sort of weird seasonal lifecycle in different climate zones. We should be learning things about the dynamics of life on this planet, but in terms of ecological philosophy the protagonists of Pikmin 4 come across as cutesy, Borrower-sized versions of the corporate marines in Avatar.

With all that said, the game redeemed itself to some extent when I tracked down Olimar and unlocked his side-adventure. It’s something resembling a stripped-down retelling of Pikmin 1, including the strict time limit, as Olimar talks you through his time on the planet prior to your arrival. It feels a bit like you’re replaying the game on hard mode, but you’re starting in different map locations and discovering the various varieties of Pikmin in a different order – taking the skills and knowledge you’ve been building up, but asking you to apply them within tighter constraints, and with unfamiliar new twists to contend with. I really enjoyed it, and I think more games should come with optional endgame remixes like this.

Aside from the enemies not respawning, I thought this was a generally pretty great game. I continue to enjoy frolicking around giant gardens as a tiny spaceman. One of the levels is set inside a house – a first for the series, to my mind. I liked the twists that came from the new environment, although I feel like they could have made more out of it, like forcing you to look for plantpots to grow things in.

Looking Ahead to 2024

I guess the first thing on my radar for next year is that there will probably be a lot more layoffs and studio closures? It’s a stressful time, not just due to the potential direct risk to myself, but also the indirect impact of so many experienced people entering the job market at the same time – competition for vacancies will be fiercer, and (one would assume) the remaining employers will be exploiting the situation to offer lower wages and so on, which will shift expectations across the industry.

But to pull this back onto the topic of what I’ll be playing, I have prepared the following shortlist of games I already own but have not played yet: Warhammer 40,000: Darktide, Company of Heroes 3, Super Mario Wonder, tons of Switch RPGs (The Diofield Chronicle, Bravely Default II, and others), Control, Persona 4 Golden, Final Fantasy X, Disgaea, Shadowrun: Hong Kong, Dwarf Fortress, Super Mario RPG (the SNES original), Dragons Dogma, some Wii games I bought over Christmas (eg. The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword, Super Paper Mario, Pokémon Battle Revolution), and Dragon Quest XI. There’s no way I’ll play all of them, but I’ll probably be dipping into this list whenever I have nothing more pressing on my mind.

As for games that came out this year but which I didn’t play, there’s Baldur’s Gate III, Diablo IV, and Street Fighter 6. I’m still hovering over the idea of buying a PS5, but I’m going to continue to wait and see what happens regarding these rumoured hardware revisions.

Finally, looking ahead at games that slated for release in 2024, I’m interested in: Destiny 2: The Final Shape, FFXIV: Dawntrail, Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth, FFVII Rebirth (although not before I play Remake), Skull & Bones (I probably won’t play it but I’m fascinated to see what state it shows up in after all these years), Unicorn Overlord, Dragons Dogma 2, Llamasoft: The Jeff Minter Story, and Thank Goodness You’re Here.