I went to Japan recently, and one thing I did there was visit the new Nintendo museum. It’s a place that lots of nerds are interested in, but it’s somewhat difficult to visit – partly because it’s in Japan, but also because it uses a complicated ticketing system to limit visitor numbers and prevent overcrowding.

Now that I’m home I thought the responsible thing to do would be to write up a description of my experience, to help people understand what to expect and perhaps help them feel better about not going at all.

Getting Tickets

There’s an up-to-date description of the process on the museum website [link], and if you’re actually planning to go then I recommend going to the site and reading the latest procedure, in case things have changed and the following description is wrong. But this seems to be the process at time of writing:

- Set up a Nintendo Online ID [link] if you haven’t got one already (it’s the same thing you use to play 3DS/Wii U/Switch games online, or to connect to the eShop, so if you’re the kind of person who wants to visit the Nintendo museum then there’s a good chance you already have an account)

- Create a Mii for your online ID, if you haven’t got one already. If you’re travelling in a group, create Miis for everyone in your group.

- Three months before you want to visit: Register for the ticket lottery draw on the museum website

- Entry for the monthly draw opens on the 1st of the month, regardless of which day of the month you want to visit, and remains open for about two weeks. There’s no benefit to registering early, but you do need to worry about missing the closing deadline.

- You can choose up to three different dates / times to visit (and my hunch is that it’s a good idea to pick three different days, if you can) – so if you’re planning this as part of a holiday in Japan, you should probably set aside a few days to be in the Osaka/Kyoto area, and be prepared to swap your other plans around once you get a firm date for the museum visit

- You can buy up to 8 tickets per successful application, so if you’re taking a group you don’t need to apply for each individual member of the group

- Two months before you want to visit: The draw takes place at the start of the month, and if you entered then you should get an email to say whether you were successful or not.

- Roughly one-and-a-half months before you visit: A second wave of tickets are released for general sale on a first-come-first served basis. I think this happens on either the 7th or 14th day of each month, but it’s very ambiguous and you might want to check every day. Also this presumably happens at a sensible time of day in Japan so if you’re in Europe it’s probably at 3am or something. Do some research and be ready for it.

- If you still don’t have a ticket: Tickets are closely tied to the purchaser’s ID so it’s difficult to resell them unofficially, but they can be cancelled and fully refunded. Cancelled tickets are batched up and re-released for sale on the hour, every hour – if you refresh the ticketing calendar [link] about 10 or 20 seconds after each hour (to allow a little time for the processes to run on the server) you will probably see a few previously Sold Out days revert to being Available, and maybe one of those dates will suit you. You will need to be ready to move fast and jump on these immediately, when they crop up.

The reason why I know so much about the dregs of this process is because I completely misunderstood the instructions on the website and missed step 5 completely (please: do some research). The good news is that, despite only having a window of 2 or 3 days when I could have gone, I still managed to get a ticket shortly before I left for my trip.

I actually think that it gets slightly easier to buy tickets as your target date gets closer, because the kind of unexpected change of circumstances that might cause a person to cancel their plans are probably quite sudden, short-notice events, right?

Also, just to reiterate: I really recommend taking the time to make Miis for everyone in your group. Everyone will get their own personalised entry pass on arrival, and having your own little Mii stamped on the front is really cute, and the generic cards you get when you don’t have a Mii look dull by comparison.

Visiting the Museum

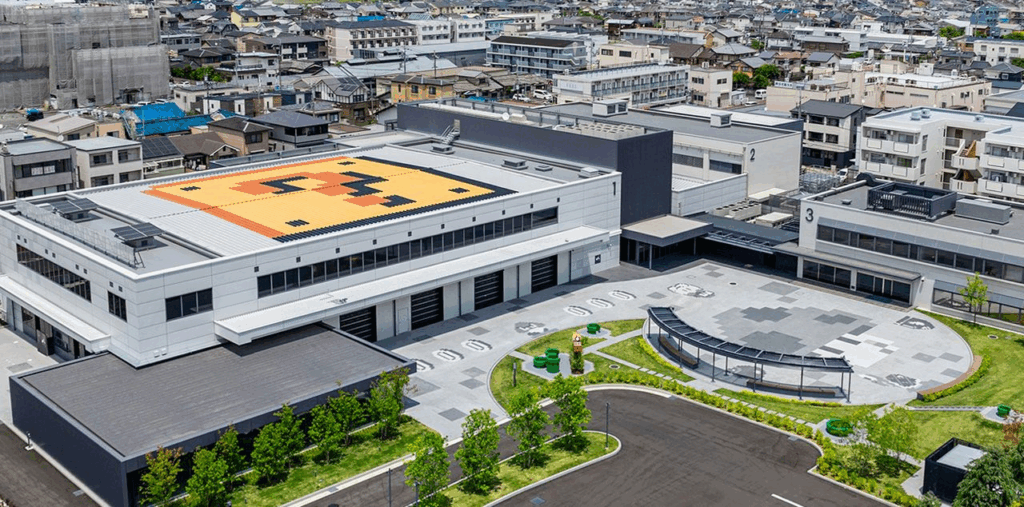

The museum is in a town called Uji, although the closest train station is Ogura – less than 5 minutes walk away. The Kintetsu line goes directly there from Kyoto station, and if you happen to be staying in Osaka you can get a train to Kyoto in an hour or less – like most places in Japanese cities, it’s easy to get to on foot.

All tickets are for a specific timeslot, and they’re fairly serious about it. If you turn up too early then they might send you away or put you in a little holding queue until they’re ready for you; if you turn up more than 30 minutes late then I would guess they might turn you away at the entrance. I arrived about an hour early, visited the nearby Book-Off, picked up a snack from a convenience store and sat on a shaded bench overlooking a small river, behind a nearby ramen restaurant until it was about time to go in.

At the entrance you go through an airport-style security check – metal detectors, x-ray scanners, and so on. You’re generally not allowed to bring food into the museum (with exceptions for baby food, people with specific dietary requirements, etc) and only non-alcoholic drinks in plastic bottles (I dimly recall being asked to drink some of my water before I was allowed in).

It seems intense, but – not to get ahead of myself, but… – if the food thing bothers you then you should know that you probably won’t be in the museum long enough for it to be a major issue, and there are plenty of places to buy food in the neighbourhood outside. There’s a café onsite that mostly sells custom burger combo meals; I’ll talk about it in more detail later (spoiler: it’s fine) but my point is just that it is there.

The other important thing to know is that photography is almost totally forbidden in the museum. There are some specific areas where you are allowed to take photos – particularly outside – but the general rule is a blanket ban. I find this very strange, but something about it tracks with the Japanese game industry’s attitude towards streaming – like the view that live gameplay is part of the game’s copyrighted content, as if streaming yourself playing a game is on a par with distributing a pirated copy of the game itself (all of which is reflected in Japanese law, as I understand it – you need explicit permission from the publisher to stream some games, apparently). The way they seem to view is it that streaming the game – revealing the unfolding story – is a form of distributing the narrative content without permission.

(For contrast: I think most western countries view game streams as a sort of ‘transformative work’ – like there is some element of this public broadcasting going on, but the human act of playing the game and the added element of having a streamer performatively overreacting to things in real time counts as an original creative work in its own right – more like an act of entertainment or cultural commentary, which puts it beyond the bounds of copyright law, or something. I am not a lawyer.)

When you think from that kind of perspective, I think it’s understandable to think of the museum’s exhibits as an assemblage of valuable information, and if visitors were walking around and taking photos of the displays and disseminating that information online – much like I’m about to do right now – then it would diminish the value of visiting the museum, which is its whole business model. So instead you’ve got this museum dedicated to joy and wonder and technology, and also a series of draconian rules to prevent you from sharing the experience with friends and family back home. I think it’s a little weird, but that’s just my opinion.

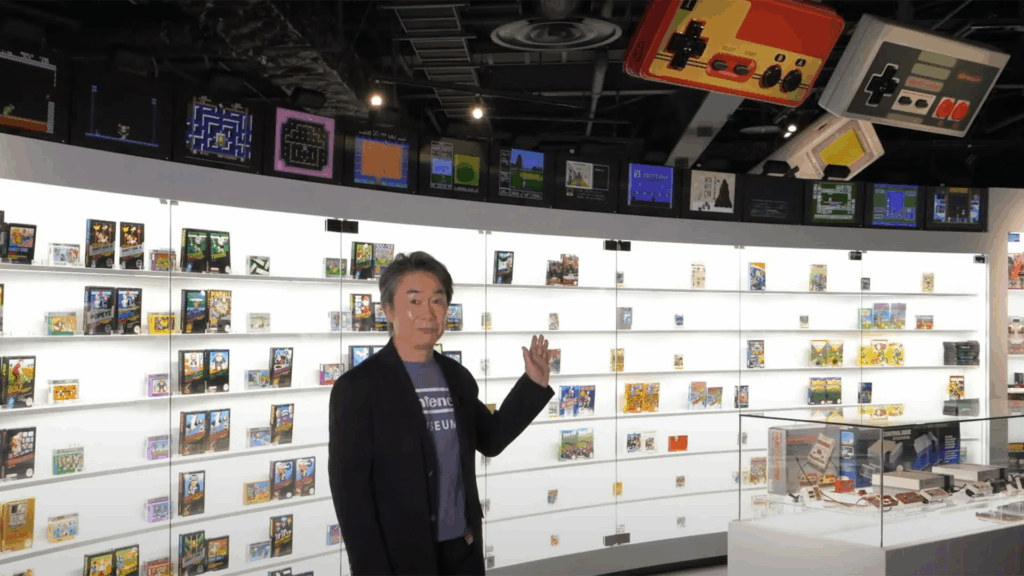

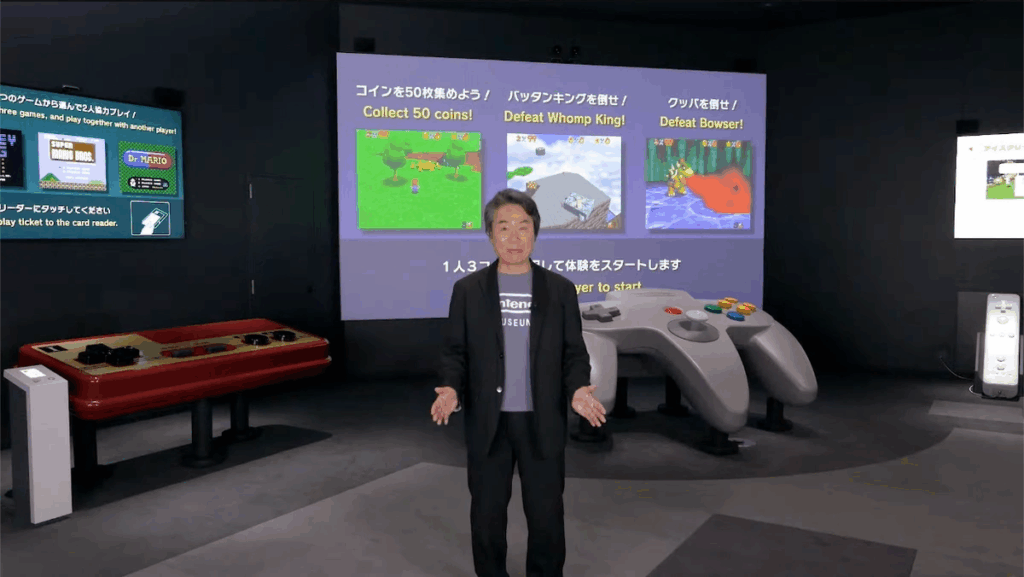

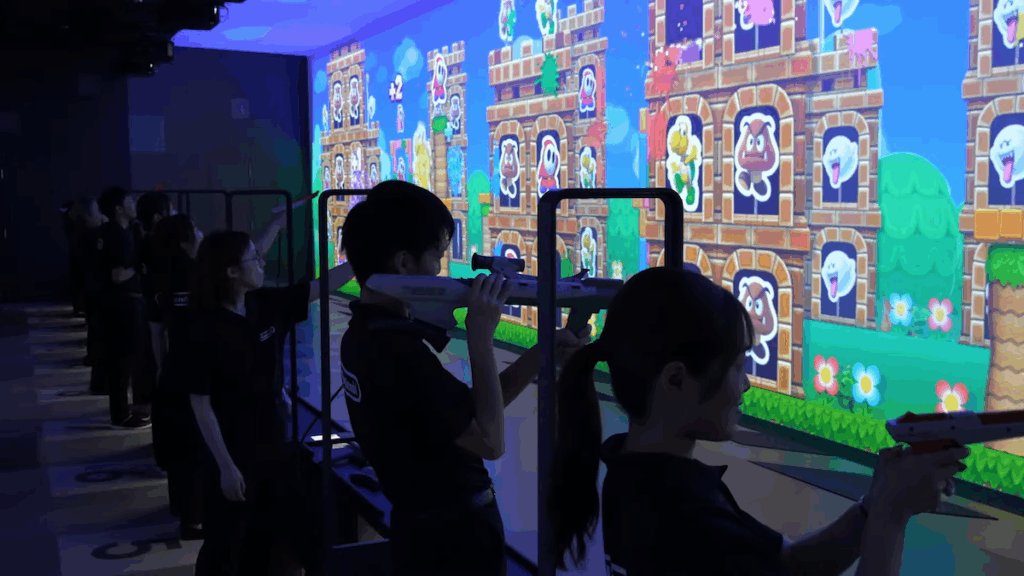

As a final twist, there are lots of photos floating around of the museum anyway – I’m going to assume these are mostly from the press visits when it first opened (during normal operations you don’t normally see Shigeru Miyamoto silently shuffling around as he tries to draw your attention to the exhibits, although it’s fun to imagine). So even though I only took a very limited number of photos while I was there, I’m illustrating this post with photos that other people took of the things I’m talking about.

The Museum – Upstairs

There are two main parts to the museum – one hall upstairs which contains all the exhibits, and another hall downstairs which contains lots of playable games. There’s also a room to design and make your own Hanafuda cards, the gift shop, and the café.

The exhibit hall is the most interesting, from a chin-stroking adult’s perspective. If you walked through it quickly without paying much attention then it would be easy to read it as a sort of product gallery – there’s a series of displays dedicated to different Nintendo consoles, with collections of mint-condition game boxes of the most successful (or sometimes, most interesting) games on each platform, usually including regional variations. I’m exactly the sort of person for whom 90’s videogames evoke a lot of nostalgia, but something about knowingly trying to trigger this feeling makes me feel a bit cynical and angry at the same time.

But no, the more interesting part are the displays that are themed around general concepts – see ‘Movement’ in the photo below, which traces a line from Nintendo’s pre-videogame days selling exercise bikes and games like Twister through to Pokéwalkers, Wii Fit, Ring Fit Adventure, and so on.

Nintendo is a company that has tried a lot of unusual hardware experiments over the years, and I really enjoyed how a display about Connectivity can tie together Game Boy link cables, the N64’s Transfer Pak, the GBA wireless adaptor, StreetPass, and so on and so on. The pace of development meant that a lot of these technologies only stuck around for a few years at a time, and they quickly become obsolete and disappear from view – especially things like the Satellaview, which were never released outside of Japan – so I think a lot of people today are completely unaware of them. It was nice to see all this stuff from different eras laid out within a little mind map of how they relate to each other conceptually.

I talk about these things sometimes when I’m trying to explain topics like the evolution of live service games. Satellaview games were only available during particular time windows while they were being broadcast, which sounds a bit like you’re downloading a game from the internet except with the same sort of scheduling restriction as a TV network – it sounds a bit strange, but also sort of fits perfectly within modern frameworks of running live events in games. Many of these old products can be read as case studies of how companies in the 80’s and 90’s were using the technology of the time to try and solve recognisable problems we still face today, and I find it very interesting to see what choices they made, what worked, and what didn’t.

Another way of putting it is that the games industry is usually focused on the present – you’re asked to buy the latest new hardware, pre-order new releases, and ignore the huge mountains of older, cheaper games and hardware you could be playing with. These kind of exhibits are like a window into a world where the games industry acknowledges its past, and contextualises its work as part of an ongoing evolutionary process. On the day I visited there was a Switch 2 on display in the middle of the room (no, we weren’t allowed to touch it) and it was probably the least-interesting thing there – not that I’m not interested in new stuff, but I felt like I’m going to be constantly hearing about it for the next 5 years anyway. For comparison, my museum visit could be the only time I get to see a Nintendo-brand exercise bike up close.

The Museum – Downstairs

Downstairs, there’s a series of playable attractions. Your access pass – the one you took the time to make a Mii for, hopefully – comes preloaded with 10 virtual coins, and you have to swipe your card and spend some coins to play the games downstairs (which, again, I assume is to limit crowding and stop people hogging the popular games). The larger attractions cost more coins, but I think they’re worth prioritising just for the novelty.

Attractions include:

- The Giant Controller Room: Giant replicas of different Nintendo controllers are hooked up to giant projector screens, playing little time-limited demos of games from their respective consoles (readers of a certain age may be reminded of that museum with a giant PC that was once featured on Bad Influence). I think the main point here is that the controllers are too big for one person to handle alone, so it’s more of an exercise in playing together with someone and trying to co-ordinate your inputs. It looked like a lot of fun, but I was there alone and didn’t fancy my chances of coordinating across the language barrier with a random stranger, so I reluctantly gave it a miss.

- The Giant Shooting Gallery: There’s a long, thin room with a huge projector screen running all the way down its length, and about 13 separate bays for players to pick up a lightgun and play a little custom shooting gallery game. Each player can choose to use either a NES Zapper (which is like a small pistol) or a SNES Superscope (which is like a big, shoulder-mounted bazooka). The game is an original creation with New Super Mario Bros. style visuals, and you just have to shoot all the bad guys you see while not-shooting the good guys who sometimes pop up. I played using a Zapper and absolutely crushed it and came in first place with 222 points – my tip is to watch the other players while you’re waiting in the queue and pay attention to which enemies score more points and when they appear.

(I’ve been looking around online and I have yet to find anyone who has scored higher, which means there is a very faint chance that I could be the actual World Champion at this game??)

- The Batting Cages: A row of half a dozen small batting cages designed to look like typical bedrooms from different eras of Nintendo’s recent-ish history. These were one of the real highlights for me! I think there’s something very thoughtful about recreating the kinds of home environments where Nintendo products were designed to be used – something about putting them in context instead of just showing them off in a glass case (as per the upstairs exhibits).

The actual game here is that an Ultra Machine – basically a small mechanical pitching arm, originally released in 1967 – lobs a series of ping-pong balls at you, and you use a padded baseball bat to smash them back across the room. The twist is that the room is rigged with lots of sensors and strange secrets, so you are encouraged to try aiming your swings to hit different objects. If you hit a TV, it might turn on and show you a clip of an era-appropriate Nintendo advert; if you hit a flower pot, some Pikmin might pop up and peer over the rim at you. It was fun!

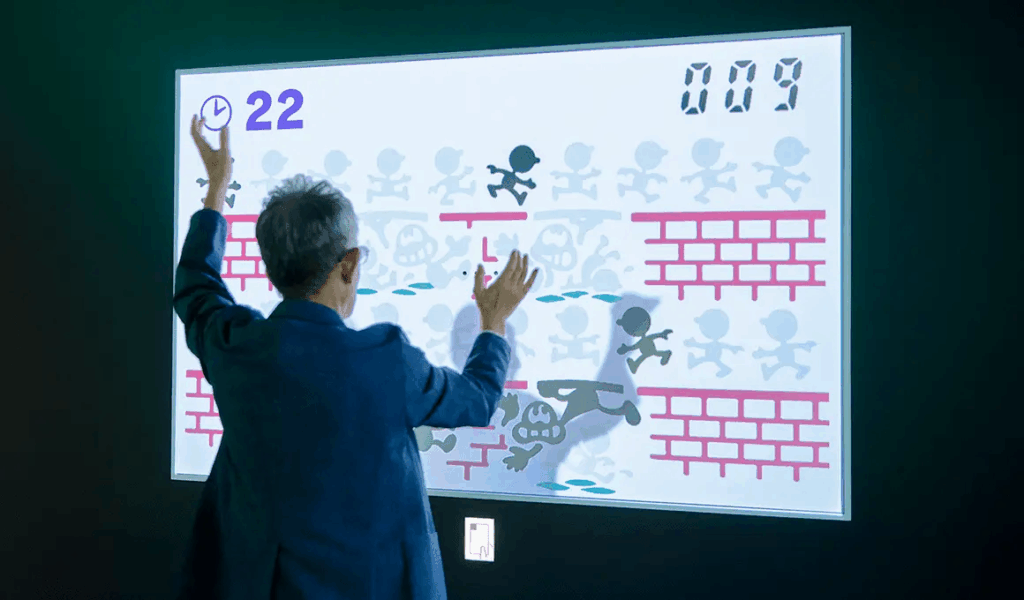

- The Game & Watch Areas: A strangely Molyneux-esque experience of casting yourself into the role of God and helping Mr. Game & Watch go about his business through the power of physical gestures. One thing I noticed was that these are often next to the queuing areas, which makes me think they’re designed as much for the benefit of an audience as the player. I didn’t play them myself, but I enjoyed watching them – to be honest, I found the Game & Watch content at the museum a lot more nostalgia-inducing than I would have expected, dredging up memories of playing on my cousins circa 1990.

- The Love Tester: A sort of giant reproduction of an old electronic game that purported to assess relationship compatibility. Presumably the original device just runs an electric charge through your body and audits your thetans or whatever, but this jumbo version seems to include some camera-controlled minigames too. I didn’t give it a lot of attention, because it felt a bit creepy to stare at couples who were using it.

- The Ultra Hand: This was a fun-looking physical game where you play as a sort of factory worker using an Ultra Hand to pluck Pokéballs and Voltorbs off a moving conveyor, and drop them into appropriate pipes – my brain is now trying to assemble some sort of I Love Lucario joke, although I can’t imagine it landing well.

- Shigureden SP: This is a tribute to an old interactive museum installation that Nintendo helped create some 20-odd years ago. In the original work you had a Nintendo DS with some unique software running on it, and you carried it around a hall trying to match up pieces of poems. This new edition is a smaller, shorter experience, and you play using your mobile phone instead of a DS, but the principle is very similar – the first half a poem appears on your screen, and you have to find the second half of the poem by walking around the room.

I avoided this because it seemed contingent on being able to read Japanese, but I’ve noticed the museum website says that players who don’t understand Japanese can play the game simply by matching the illustrations on the cards.

- The Normal-Size Controller Room: A large number of stations are set up with different consoles and either 1 or 2 controllers, and you simply pay 1 coin to get 7 minutes of play time. When I first walked around this room it seemed the most pointless to me – all the games available are the kinds of classics that Nintendo keep re-releasing via virtual consoles, not to mention all the less-than-legal means by which people could access them for free – but after a while I remembered that most people don’t have massive collections of old games and hardware lying around at home. For a lot of young kids these games might be strange new experiences, and for older visitors they might be games they haven’t played for 30 years.

I think once I got past the novelty of giant-sized controllers and what-not, it the was the Normal-Size Controller Room that had the greatest affect on me. It feels like the crux of what the museum offers, in some ways – a big room celebrating Nintendo games between 1983 and 2002 – and there was something very sweet and nostalgic about playing Pilotwings and Super Punch-Out for 7 minutes each.

But before this turns into one of those nauseating AI-generated mythological gaming nostalgia images, let’s take a moment to reflect that what I’m nostalgic for is less to do with the games themselves, and more to do with the period in my life when I was playing the games originally. Maybe this is one of the things that left me feeling a little cold about the museum – precisely because I am one of those middle-class millennials who grew up with Nintendo games, there’s a key element missing from the museum which is my friends from school who I used to play with. I was left with a sort of melancholy feeling like “I used to be happy and carefree, and those days are never coming back.”

It is on this note that we enter the gift shop.

The Merch Annex

I was half-expecting to spend a lot of money here – there are a number of items that are exclusive to the museum, and in particular they put per-customer purchasing limits on some things to stop people from buying them up in bulk to sell online, so there’s a lot of hype and mystique around the place.

The giant squishy controllers are probably the most iconic examples, and there is probably a version of the world out there where I flew home using a giant squishy SNES controller as a pillow on the plane, but these things are about £60 each and I couldn’t pull myself away from seeing it as a pointless novelty. Maybe worthwhile if I was looking for stuff to decorate the background of a streaming studio, but I’m too Northern to spend £60 on, essentially, a cushion that nobody would be allowed to use. I decided I would rather use the money to buy something practical once I got back into the city. That’s the kind of Nintendo fan I am – the real kind.

There is a range of t-shirts, mugs, pens and pins representing different Nintendo consoles, and I do think they were quite tastefully designed, but they also very much looked like stuff that booth attendants would wear (or drink from, or write with, or just hand out) at a trade show. The thought of paying money just to dress myself up as a PR rep rubbed me the wrong way, so I kept on walking.

They had some nice sets of Hanafuda cards – another museum exclusive – which came out at the top of my mental list of classiest things to buy at the Nintendo Museum shop, except… these were also very expensive. I feel like the price was a bit more justified here, because at least the cards seemed genuinely well-made and nice to look at (as well as being a deep cut into Nintendo’s history) but I still couldn’t bring myself to buy an expensive deck of cards for games I don’t know how to play, just for the sake of pulling them out of a drawer every few years to show a visitor. Still, here’s a photograph from someone who did buy them. Nice, right? Tasteful. If you’re looking for collector’s item to take home, I think these are a better choice than the giant squishy controllers.

Beyond these, I think most of the rest of the items on offer were non-exclusive items that I had already chosen not to buy at the Nintendo store in Osaka. Do you want a Donkey Kong onesie? A warp pipe filled with small, individually-wrapped cookies? Me neither. Some of these things were nice – I did waver over whether to buy a big squishy Yoshi egg, which was just the right size to throw at a rival during a heated game of Mario Kart – but I chose to pre-emptively Marie Kondo them out of my life before they entered it.

On some level, I just wanted something unusual to take home as a memento of my visit. Then final nail in the coffin for the gift shop came when I realised the museum’s access card – the one with my name and my Mii-rendered face on the front, stamped with the date and time of my visit – was already the perfect item to fulfil this role, and I already had that in my pocket. It made me appreciate the overall museum experience more, though – it was nice to think that the cost of entry automatically includes a little personalised keepsake.

The Café

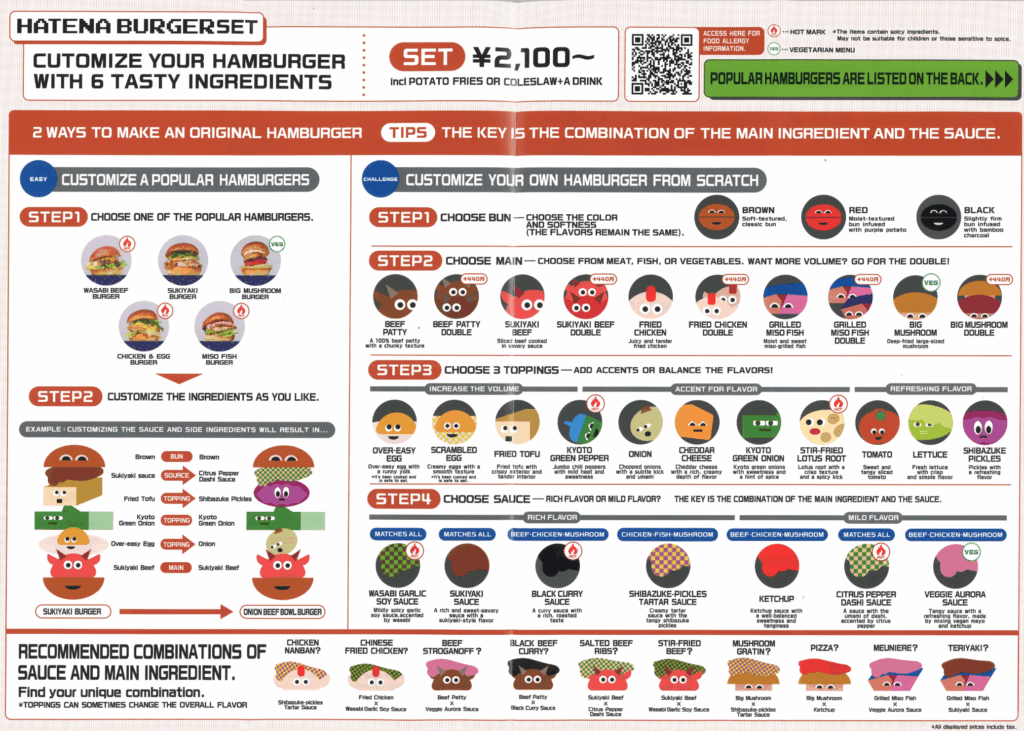

The main thing they offer at the café are these customisable burger meals, which at ¥2,100 are about £10 each at time of writing. You have to scan a QR code (which I hated) to access a link to their burger customisation system, and then take a minute (which I hated) to tap through a series of screens to select what kind of bun you want, what you want sandwiched inside it, a side, and a drink. There was a lot of information to take in, and I felt a bit flustered when I was trying to assimilate the available options and make my choices while a queue of hungry families stood behind me.

All in all I basically hated the whole ordering experience, and the food never got beyond okay. I felt like I would have preferred to buy dinner at a convenience store, but to be honest once I got inside and was jimmied into the queue by a greeter, I felt like I may as well ride out the experience for the sake of reporting back about it here.

The cafe was okay. There were some nice pictures on the wall, and a big stained glass window of Link surrounded by other Zelda characters. I didn’t enjoy the ordering process, but once I had my food and could sit down and have a moment to myself, I didn’t feel too bad about my decisions – in real terms the price wasn’t so bad, but it felt like a lot compared to a typical convenience store picnic.

The Hanafuda Workshop

One of the more interesting features of the museum is that they put on little group workshops to make your own decks of Hanafuda cards. However: I didn’t sign up for this and have no idea what it’s like inside.

I’m only bringing it up here to emphasise that it does exist, and apparently it’s very good, and if you want to do this you should sign up for a session as soon as you get inside the museum, or so I am told.

Final Thoughts

I can understand people saying that the Nintendo Museum is underwhelming. It’s quite small and simple, and only takes an hour to get round – maybe two, if you spend a long time pondering the exhibits and mulling over which games to play. I think people generate a lot of their own hype for the museum based on what Nintendo nostalgia means to them personally, and when they get there it turns out this is a modest look back over a history of the company from a very practical, product-focused perspective. This is not a Mario museum, or a Zelda museum… if you want an immersive fan experience, try Super Nintendo Land over at Universal Studios Japan, in Osaka.

I felt close to regretting my visit while I was walking around the interactive games area and wondering what to spend my coins on. But I think there’s plenty to enjoy here if you take it on its own terms, and – crucially – it’s only about £15 to enter, which feels like a very low price. So I think my verdict would be that it is worth visiting if you have the opportunity, but you need to pay close attention to the ticketing process, and you should have modest expectations about what it will be like and how it will fit into your day – starting from central Kyoto, you could go to the museum, see everything and catch a train back within 2-3 hours.

(If you’re looking for other things to do in Kyoto – particularly if you’ve got kids with you – may I recommend Toei Studio Park?)

Nevertheless, it’s interesting! The exhibits upstairs feel a bit thin on context, but they are comprehensive. The playable games downstairs are unique installations that will probably justify the visit on their own if you’re a big nerd. The shop does have a bunch of exclusive items that are otherwise only available from scalpers who are selling them for 3x the price online. The Hanafuda workshop might be (??) a memorable little creative break on your holiday – that time we painted flowers and animals on some tiny cards and learned to play Koi-Koi. The café… exists. You will hopefully walk away with a cute little personalised access card with your face on it, to commemorate the occasion.

Ultimately, your time there will going to come and go quicker than you might expect – this is not going to give you some cathartic emotional payoff for decades of being a loyal consumer of the Nintendo brand. Mario is not going to pop out of a pipe and give you a hug. And that’s okay.